Fitzhugh Hastings Pannill, my father, was born January 15, 1916, in Stephenville, Texas. He received the names “Fitzhugh” to honor his uncle Fitzhugh Carter Pannill, and “Hastings” to honor his uncle William Hastings (husband of my grandfather’s sister Margaret). Dad died July 22, 2000, at age 84.

Fitzhugh Hastings Pannill, my father, was born January 15, 1916, in Stephenville, Texas. He received the names “Fitzhugh” to honor his uncle Fitzhugh Carter Pannill, and “Hastings” to honor his uncle William Hastings (husband of my grandfather’s sister Margaret). Dad died July 22, 2000, at age 84.

The Rev. Lawrence P. Gwin, Jr.

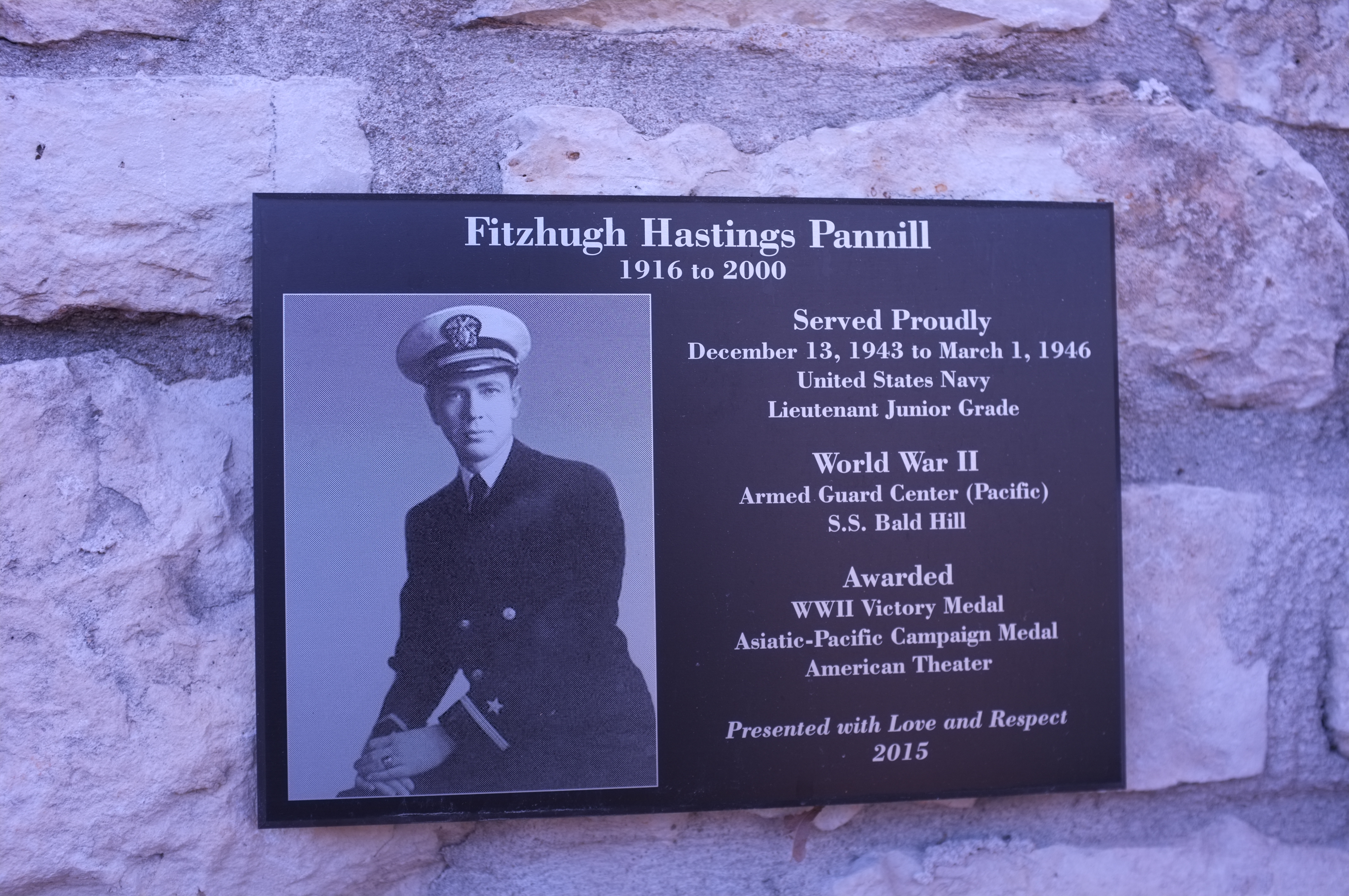

On January 15, 2016, the one-hundredth anniversary of Dad’s birth, members of the family dedicated a plaque to commemorate his service in World War II. The plaque hangs at the National Museum of the Pacific War in Fredericksburg, Texas.

This is one of the finest military museums in the world. The collection occupies a modest building adjacent to the family hotel in which a teen-aged Chester Nimitz, later a 5-star Admiral of the Fleet, worked as a desk clerk before his appointment to Annapolis.

At the personal direction of President Roosevelt, Admiral Nimitz took over as commander–in-chief, Pacific, following Pearl Harbor. He toured the destruction in the harbor on Christmas Day, 1942. When he finished, he said the Japanese had made three mistakes:

1. They attacked on a Sunday morning, when 90 percent of the ships’ crews would be on shore leave.

2. They attacked Battleship Row instead of the dry docks opposite, which made repair of most of the ships readily available.

3. They failed to attack the oil-storage tanks over the hill from Pearl Harbor, which contained “every drop” of fuel for the fleet in the Pacific.

Taken from Grunt.com (2011 blog). Admiral Nimitz resurrected the Pacific Fleet, which went on to victories at Guadalcanal, Midway, and the long island campaign leading to the Japanese mainland. He ensured victory over Japan. He was one of the nation’s pre-eminent heroes of World War II.

After the war, a delegation from Fredericksburg called on the admiral – living in retirement in San Francisco — for permission to open a Nimitz Museum. He refused. They made more visits. At last Admiral Nimitz relented so long as the museum was not about him but the men who had served under him.

The old Nimitz hotel sits on the main street in Fredericksburg as museum headquarters. But a courtyard connects the hotel to a new museum at the back of the property. This is the George H. W. Bush Gallery of the Nimitz Museum. It is the place to start, with hundreds of exhibits, interactive tables of battles, and explanations of the Pacific War.

The first President Bush, who served under Nimitz as the youngest pilot in the Navy and a pilot of a TBM torpedo-bomber, dedicated the new building in 2009. Inside, one of the exhibits shows film of a 20-year-old Lt. (jg) George Bush being pulled from the Pacific in 1944 near Iwo Jima, where he had ditched his burning plane after completing his bomb run. His two crewmen both died.

From left: Cheryl Smith, Jack Smith, Shirley Smith, Al Goodrum, Judy Merino, Henry Merino, Jr. William Pannill, Richard Collier, the Rev. Mr. Gwin, Molly Hammond

In the courtyard that connects the Bush wing to the Nimitz wing, the museum has hung dozens of plaques for individuals, ships, and units in the Pacific war. Any Pacific veteran’s family can commission one.

Dad was not a war hero, but he served honorably as a Naval officer. He took the train from Fort Worth in the fall of 1943 to attend Officer Candidate School in Tucson, Arizona.

We have home movies of his departure from Fort Worth train station. The scene lasts only a minute, but it shows him in an officer-candidate’s uniform as he walked to the train with his father, Judge William Pannill. Mother, my younger brother Fitz, and I brought up the rear.

Dad was 27 on January 1, 1944, the date of his commissioning. He had practiced law for five years with the Ohio Oil Company. We had moved with him to Marshall, Illinois, when he replaced a lawyer there named Carl Albert, who had enlisted in the Army. Albert went into politics in Oklahoma after the war and became Speaker of the United States House of Representatives in 1971.

The Navy assigned Dad not to its legal branch – the judge advocate general — but to the Naval Armed Guard. He attended Armed Guard School after he finished OCS.

The Naval Armed Guard furnished guns and gun crews to merchant ships.

Dad was commissioned an ensign and trained at the Navy’s Armed Guard School. He then took command of the Naval detachment on the S.S. Bald Hill, an oil tanker plying the Pacific coast.

A base in Maryland stores all the Armed Guard reports from the merchant vessels. I plan to obtain copies; I was three when he became a Naval officer.

I do remember visiting the Bald Hill in a California port, climbing the ladder up to the bridge, and looking into Dad’s quarters. I have a couple of 78-rpm recordings of me and my brother Fitz (aged four and two) that we sent to Dad while he was at sea.

His assignment was not safe. A Japanese submarine could have blown an oil tanker to kingdom come with one well-placed torpedo. By 1944, however, the Japanese submarine fleet was doubtless degraded.

At any rate, the crew trained regularly with target practice in case the tanker encountered an enemy vessel. By the end of his life, Dad was quite deaf, perhaps because of all the gunnery practice.

The Navy promoted Dad to lieutenant, junior grade, which is the equivalent of a first lieutenant in the other services. When the war ended, the Navy transferred him to New Orleans to discharge sailors, while the rest of the family returned to 2223 Colquitt in Houston. V-J Day was September 2, 1945. He left active duty in March 1946.

Dad brought some war booty home with him, which us growing boys played with over the years. There were shells and shell casings, a fur-lined pea jacket in which he stood watch (stolen from my Ford convertible in Boulder, Colo., in 1960), and a Bluejackets Manual from 1941 or so, which I still have. There were also shoulder boards and a Naval identification card. The uniforms and hats have been lost.

Plaque to honor Lt. (jg) Fitzhugh Hastings Pannill, U. S. Navy Reserve 1944 – 1946

You can view Dad’s plaque along with all the others at the museum’s website, http://www.pacificwarmuseum.org/get-involved/memorials/ Look under Wall Plaques for Fitzhugh Pannill. Every plaque gives you a sense of the men who fought the war.

4 Responses to A hundredth-birthday tribute

A wonderful tribute!

Thanks. Time to meet.

What a lovely tribute to a fine man!

Really interesting Bill and thank you. The Nimitz Museum is on our Texas bucket list.

John T. Cabaniss

Retired Senior Partner