The Culpeper Times, a newspaper in Virginia, offered us a glimpse last week into the lives of two Pannills from the Revolutionary war. Since we had just watched the first of the HBO series John Adams, the article took me back to the 18th century.

The American Revolution ended with the Treaty of Paris in 1783. One of the provisions of the treaty allowed British merchants to recover outstanding debts from their former colonial customers.

Yet not until 1800, 17 years later, did any authority appoint agents to attempt recovery of the debts. Julie Bushong of the Culpeper County Library wrote in the Times about the reports of one such agent, a Richmond man named William W. Hening. Hening tracked debtors in Culpeper County, which lay north of the Rapidan River. The article appears on line in the November 27 issue at CulpeperTimes.com.

Hening had a difficult task to find the debtors, Ms. Bushong writes. Some debts were 30 years old. Debtors had moved or died. Others had no means to pay with. To search, Hening interviewed relatives, neighbors, and acquaintances of debtors. The British government has preserved his reports in the National Archives in London.

One of his reports acknowledged the help of William Pannill, of Orange County, and his wife, Ann. Ms. Bushong quotes the report:

In all the forgoing [sic] claims where Mr. Pannill’s name is introduced as my informant, I am equally indebted to his lady, Mrs. Ann Pannill, for the information she communicated. She possessed the most retentive memory of any person with whom I have yet conversed on the subject of British debts. Mr. Pannill is one of the most celebrated farmers in our country. He and his wife have resided on the same estate for near forty years.

“This is a little gem of a statement,” Ms. Bushong writes, “as it is very rare to find credit given to a woman in this manner in such documents from this era. . . It is easy to imagine that Hening found much hospitality and counsel at the Pannill home while he performed his thankless job.”

This couple are among my fifth great-grandparents. Ann Morton Pannill was the daughter of Jeremiah Morton of Orange. Her husband was William Pannill III. Ms. Bushong writes that the Pannill estate lay along the Rapidan River and that William Pannill was “a prominent citizen of Orange County until his death in 1806.”

There is a problem with the last statement. In fact, the Pannill farm did contain several hundred acres and lay about a mile south of the Rapidan. William’s father, William Pannill II (1690-1749), had built the original house (which I have seen) in the 1730s, and the house still stands. Two family cemeteries lie on the grounds near the house. The name of the farm was Green Level.

The family properties appear in Confederate engineer’s maps of the Civil War. And I have been told that Green Level remained in the Pannill family until 1948.

Orange County was organized in 1734. I have also been informed that William Pannill II built the house at Green Level using bricks dragged overland from Williamsburg. His widow, Sarah Bayly Pannill, had borne him several children, one of whom was William Pannill III (b. 1738). (Sarah Bayly remarried after the death of her husband and became the grandmother of President Zachary Taylor. See the post Did Zachary Taylor meet our cousin at the White House?, November 12, 2012))

William III took a large part in the American Revolution. My research shows that on appointment to the vestry of the Anglican parish in Orange about 1768, William III took the oath of allegiance to George III. In the 1770s, he was elected to the County Council as one of seven or eight “gentlemen.” Orange County was then the largest county in Virginia, extending, by some measures, to the Great Lakes.

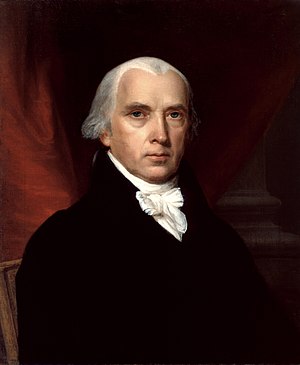

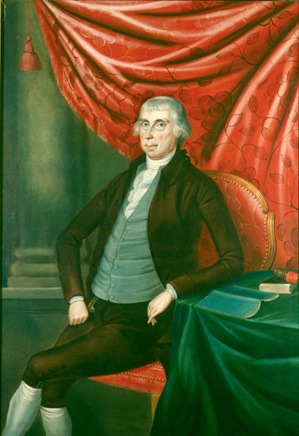

James Madison, Hamilton’s major collaborator, later President of the United States and “Father of the Constitution” (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

The head of the County Council was James Madison, Sr. By 1774, the future President, James Madison, Jr., aged 23, had joined the Council as its secretary.

In 1776, William III became a revolutionary, and the Council reconstituted itself as a Committee of Public Safety. W. W. Scott’s History of Orange County, Virginia, states:

The committees of safety were very great factors in the war, and really constituted a sort of military executive in each county.

William III did not fight in the Revolutionary Army. In 1776, he was 38 years old. Nonetheless, Scott writes,

Membership of the Committee was quite a badge of distinction, and descent from a Committeeman constitutes a clear title to membership in the societies known as “The Sons” and “The Daughters of the Revolution.”

These are not the same societies as the Sons and Daughters of the American Revolution. My hearsay information from a member holds that to be a member of the Sons or Daughters, your forebear must have been one of the revolutionaries whom the British would have hung had they won the war.

By the way, William’s youngest brother, Joseph (b. 1749), seems to have emigrated to Georgia. Joseph would have been 27 in 1776. He would have been nearest in age to his mother’s Strother daughters. That may account for the name of President Taylor’s younger brother, General Joseph Pannill Taylor of the Union Army. Joseph Pannill did fight in the Revolutionary Army and rose to the rank of colonel. As a result, Joseph Pannill’s descendants may claim membership in the Society of the Cincinnati, which consists of descendants of officers in Washington’s army.

The problem with Ms. Bushong’s article lies in her date of William III’s death of 1806. My sources at Ancestry.com show a date of death for William III of 1789. If Ancestry.com shows the right date of death, Hening could not have interviewed William III.

Ms. Bushong’s article distinguishes between William III and another William Pannill who, she writes, “migrated to South Carolina.” She says the two “are sometimes confused on genealogy webpages.”

This is the first I have read of a William Pannill migrating to South Carolina. William Pannill IV, one of Ann and William’s children, was born in 1768 at Green Level, according to the family trees at

Ancestry.com. At some point, he moved to North Carolina, where he purportedly died in 1835. I have read that he helped establish the University of North Carolina.

But William IV would have been 32 in 1800. I know of no date for his move to North Carolina. Yet it seems unlikely he would have headed for North Carolina in his mid-30s.

Moreover, Ann Morton Pannill (1736-1804) was his mother. Hening’s report calls her “his lady,” but he could not have mistaken her for her son’s wife. She was 64 in 1800, twice his age.

The family trees at Ancestry.com, the source of my dates, can certainly contain errors. The site publishes documents but also relies on shared family trees. I have encountered in some trees children purportedly born to mothers in their 50s and 60s, or contrariwise, to mothers of 8 and 10. You have to check the Ancestry hints with care.

But I have not found a William Pannill who died in 1806. Undoubtedly I need to polish up my research. I’ll have to try to figure out which dates are correct and which William Pannill Mr. Hening did talk to.

11 Responses to The perils of genealogy: when did William Pannill III die?

William,

Thank you for the information.

I am one of those Pannells that comes from the South Carolina William-Anderson-Littleton-Andrew Jackson Roden Pannell-Thomas I-Thomas II-Thomas III to Me.

It would be interesting to know the whole story. I have read your article where DNA ties you to the Pannell (Some Roden Named) clan with ties in Monroe, County, TN.

Thomas Pannell IV

It’s likely we are kissing cousins. I’ve just ventured on to Ancestry.com in the last month and have much verification ahead before I claim my FFV badge, but all branches lead to Virginia by way of Monroe County TN. Even to Orange VA. That’s why some of my Jackson relatives in Illinois, including Uncle Orange (who — sorry — fought for the Yankees), have that curious first name, I bet. And I had been hoping it linked me to the House of Orange.

Nancy Beth Jackson

I don’t doubt Orange County was named for William of Orange. Pannills have lived there since the 18th century, so we probably are cousins (no Union monument in Orange, though).

I am related to you as you are a “brother” Marine! I was in Plt 374, and left as you did in a green bus for San Onofry. Our D.I. Meade us do push ups on the way, ” just so he could say he did it! I was in “Mike” Company at ITR. Semper Fi !

I never knew the names of the DIs in Platoon 374, although we could observe you all every day in the next set of Quonset huts. The one I remember is a burly blond with a crew cut, a short forehead like a Neanderthal, and a mean look. We had several of your boots in Charlie Company, whose names have all left me, although the faces remain. One of the great stories I heard was from one of your boots who was sitting on his bucket and cleaning his M14 on the company street on a Sunday morning when the duty DI charges out of the duty hut shouting, “Who’s this [expletive] who’s got 17 years of education?” The DI had been reading through the service-record books in the duty hut. The boot had been a philosophy major at the University of San Francisco and then gone through first-year law school. The DI had him report (he runs up, comes to attention before the DI, and screams, “Sir, Private _____ reporting as ordered.”) The DI asked him what he had studied.

“Sir, philosophy.”

“Philosophy? What’s that [expletive]?”

The DI ordered the boot to recite all his philosophy courses while running in place.

“Sir, ethics, epistemology, metaphysics, axiology, ethics, aesthetics, logic, politics.”

Only in the USMC. Do you have a yearbook?

When someone writes an article he/she retains the

thought of a user in his/her mind that how a user can understand it.

So that’s why this piece of writing is outstdanding.

Thanks!

You’re welcome.

Hi, Mr. Pannill,

I inherited from my mother an heirloom sampler made by Mary Pannill (“born January 29th 1789”) in honor of her parents, “William Pannill and Ann Morton married March 3″. It depicts a house which might represent Greenlevel and possibly the gravestones of her parents (marked”AP” and “WP”). I would be happy to send you a photo if you email me.

Ann M.

I would love to have a picture of the heirloom sampler. My email is fljen69@yahoo.com

I found the copy I received from our cousin and will send it by email.

Hi William. I have an 1807 receipt signed by Zachary Taylor (future president) in Louisville, KY. It is for a plat for 400 acres made by surveyor Richard C. Anderson for William Pannill. I wonder if this is William Pannill (1768-1835), who was from Orange County, VA. He was a half first cousin to Zachary. Some researchers say William and Martha Pannill later moved from Virginia to Kentucky, where he died. Does anyone have more information about William’s move to Kentucky? thanks, Tim